It seems I can’t escape my confusion with money and I had to race off first thing in the morning to get more out to pay for the hidden entrance fees on my tour. Apparently all I have paid for is the bus and guide - the agent I bought my ticket from obviously forgot to mention the other 70 Bolivianos (AUD$35) I must produce to get into the National Park areas.

I eventually get back onto our cozy tourist bus, and we pick up various people around town, almost filling all of the velvet blue velour seats. The street sellers are already clustered around the main square, Plaza de Armas, and its lesser sister-square, trying to convince anyone who looks remotely like a foreigner to buy their jumpers, scarves, batteries and massages. People complain about the aggressiveness of their tactics, but I have been to Bali: I have seen much worse.

Our first sight is Sacsayhuaman (pronounced “sexy woman”) - the Incan walled complex – which, at only a few kilometres out of town, we pass by without stopping. Our tour guide takes this marker though, as an opportunity to begin a short history on the Incans. We are told that over 8 million of them existed at their peak, but that contrary to popular belief, most of them were not killed in battle with the conquering Spanish, rather, forty per cent actually died in the sixteenth century from syphilis (although various other web sources say it was a combination of smallpox, typhus and influenza).

We are also told how gold was not seen as important to the Incans (only used for decoration of tombs, temples and ceremonies), but that it was a different story for the Spanish, who immediately used the Incans as slave labour to extract it for trade and wealth. We then start our descent into the Sacred Valley where maize covers the fields of almost all available space, providing ample fodder for local beer production, and company for the many scattered cacti.

Our first stop is at the pueblo C’orao – which in Chechuan means grass, and was the original Incan place for llama sacrifice. But all we find here is a typical souvenir market, set out in eight identical rows, and a scruffy looking man selling photos with his glazed llamas (who is a bit too quick to remind me that I have to pay for the privilege of each shot). A sign behind him announces the opening times as Tuesday, Thursday and Sunday, and I suddenly realise why these are the only days that tours are available too.

I get back on the bus with another pair of colourful llama legwarmers - who can resist their fluffy warmth? – and we pass through more villages that have been hit by successive earthquakes (1350, 1650 and 1950), strangely consistent in their devastation. Eucalyptus trees spread themselves once again across the unfamiliar landscape and our tour guide informs us that they were planted in nineteenth century to stop the effect of erosion, during their six month-long rainy season (October to March). We are also told that people chew the leaves too, for its medicinal properties, but I can’t help but smile when I think of all the koalas that do the same, and drop out of trees completely high.

As we drove on, I looked out at the mud-brick adobe gateway leading to nowhere, at the steppes climbing their way to the top of monstrous deep-wrinkled mountains that frame the sides of the valley, and breathe it all in. We stop at Mirador Taray to get the best view of the Sacred Valley, which, at more than 200km long, was so named because the Incans believed it to have the most fertile soil. The Urubamba River twists and turns its way throughout the panorama, all the way to foot of Machu Picchu.

Next we arrive at the town of Pisac – 32 kms from Cusco – self-proclaimed on an entering wall mural as the artisanal capital of Peru. But it’s really just another larger winding market, and so the only thing I buy is food. I taste my first wholemeal empanada which is definitely the worst I have had yet, and take a further punt on an alfajore-look-a-like that tastes more like a hammy Tartaric acid than dulce de leche. I guess the fertile soil hasn’t really been put to such good use after all.

Fortunately there is choclo (literally “corn”, but a savoury version of our sweet vegetable) and fried cheese (much like haloumi) at the next archaeological site of the Incans and where are told that the terraces carved here formerly produced a range of hot (fruits, coca leaves) and cold (potatoes, barley and wheat) goods at the bottom and top levels respectively. But the relentless snaking path starts to hurt my head and tummy soon and I can’t help but curse the intelligence of the Incans for not realising the beauty of tunnels. Add to this the inane repetition of Blondie’s “Call Me”, which is apparently the only song the driver has, and I am well and truly ready for our ‘typical’ Peruvian lunch.

That is until I saw the garish orange-clad Pocahontas-esque girl waving us down at our destination. Now I am not sure if it was the clip-on black plaits that she wore, or the looks that she copped from traditionally dressed locals that put me off, but I was not really in the mood to pay 35 soles (AUD$18) for an all-you-can-eat banquet being served to pan flute renditions of the Beatles and Phil Collins. The restaurant next door, with its 8 soles (AUD$4) three course menu was, in my book, much more authentic.

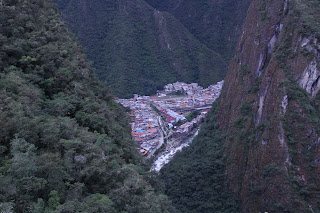

From here we head to our final two destinations – Ollantaytambo, the incomplete gatekeeper town of Machu Picchu and Chinchero, a former Incan town - believed to be the birthplace of the rainbow - transformed by the Spanish when an adobe colonial church was built on its former ruins. I can’t resist bargaining for some carved wooden kitchen tools before scoffing down another choclo and cheese combo, and a meat stick and heading back to the bus. It will be an early start tomorrow, and a few heavy days of walking, with the start with the Inca Jungle Trail and my pilgrimage to Machu Picchu.